You can find the video recording from the webinar here and presentation PDF here.

Please note that similar questions have been combined and summarized.

Questions about SOSS

Does SOSS show the price per kg at the station? Should you call the station?

SOSS displays station’s location and status information. It does not currently display price per kilogram, but our members are in discussions about adding this information. The station operators ask that you only call the phone number if you need technical support.

Do you plan to use SOSS to track the amount of hydrogen each station dispenses daily and/or on a cumulative basis?

Stations that receive state funding already report the amount of hydrogen dispensed to the California Energy Commission via the NREL data collection tool; CEC includes that information in its annual report published in December. NREL publishes aggregated data on its page Hydrogen Fueling Infrastructure Analysis. The following is the 2017 report and we will send an email blast when the 2018 report is published.

Will SOSS display the capacity of the station?

Yes. SOSS currently collects the capacity and now has it displayed by default without the need of logging into the system. To view the available KG of hydrogen at a station on SOSS, click on the station of interest to find it directly under the status for each pressure.

Questions about Station Technology

What is the different between H35 and H70? Why would you use H35?

The numbers refer to the pressure of the fuel, measured in megapascals. For example, H35 = 35 megapascals = 350 bar = 5,000 PSI and H70 = 70 megapascals = 700 bar = 10,000 PSI. Existing stations were designed to fill at both pressures because—at the time—some of the cars used only H35 and we assumed that the stations would also fill trucks and buses, which use H35. Now, passenger cars use H70 and additional market research indicates that trucks and buses will likely use a separate station or a separate dispenser. Newer stations, like Anaheim and those under construction, have only H70.

At times, when a station has limited pressure and can’t dispense H70, you can get ½ tank (or less) from the H35 nozzle.

Currently, all fuel cell buses use H35 and most of the fuel cell trucks use H35. Toyota’s Portal truck uses H70.

Can the same station serve cars, trucks, and buses?

Generally, no. Cars and heavy-duty vehicles use different fueling protocols. Currently, the UC Irvine station fills the UCI fuel cell bus and has filled OCTA buses.

It is thought that some connector stations will serve several categories of vehicles, including heavy duty and light duty. Nikola Motors, for example, has indicated that it intends to fuel trucks and passenger vehicles at its stations.

In most cases, hydrogen infrastructure for transit buses will likely not fuel other categories of vehicles, given issues related to the locations and footprints of transit operations, and the fact that fueling other categories of vehicles may not match a transit agency’s business case.

In CaFCP’s Medium- & Heavy-Duty Fuel Cell Electric Truck Action Plan for California (page 11) the plan states, “A medium-duty parcel delivery truck will need approximately 10 kilograms of hydrogen; more than twice the capacity of a passenger vehicle. Fuel cell trucks will need high-capacity stations, meaning that they store 500/kg or more of hydrogen and can fill vehicles back-to-back in less than 10 minutes per vehicle.” It is possible that passenger fuel cell cars and fuel cell trucks may fuel at the same site, but not the same pump, like truck stops do today.

Can you have a station on wheels that fills cars?

Yes, but the current thinking is that it’s better to build more stations to reduce costs and increase the number of vehicles. Potentially, one hydrogen station can fill one hundred cars a day, but a mobile fueler might only fill 10-20 cars a day. A mobile fueler that comes to your house or office would be very convenient, but for now we need stations that fill larger numbers of cars.

CaFCP member Ivys Energy Solutions won DOE’s H-Prize for SimpleFuel that targets “opportunity fueling” for cars and material handling.

Can you elaborate on onsite storage and fueling positions at hydrogen stations?

Each station developer has its own design for storage, compression, and dispensing hydrogen, and the design can vary slightly from site to site. The following fact sheet is an overview of different configurations with the advantages and disadvantage of each.

Most of the stations operating today store 100-200kg of hydrogen onsite and have one dispenser with one H35 and one H70 nozzle. Most of the stations under construction will store more hydrogen onsite (200-500kg) and have multiple fueling positions; two dispensers and/or two H70 nozzles that can be used at the same time.

Does station equipment footprint hinder adoption?

Somewhat. Because hydrogen station equipment is all above ground, it does need more space than gasoline storage. And not all existing retail gas stations have the available space to accommodate hydrogen equipment. (See Sandia’s Safety, Codes and Standards for Hydrogen Installations: Hydrogen Fueling System Footprint Metric Development, page 19.) Today’s stations require less space than the early development stations and the size and placement data that will continue to evolve.

Is CaFCP working with equipment providers to develop a fuel cell nozzle that doesn't freeze up?

We first talked about the frozen nozzle problem in October 2017. Hydrogen is cooled to -40°C so it can be quickly dispensed. Cold hydrogen turns moisture in the air into frost on the nozzle and receptacle. Sometimes the frost becomes ice—particularity after back-to-back fills—and the cold metal of the nozzle latching mechanism freezes.

WEH and Walther, the companies that manufacture most nozzles are working with automakers and station developers to find solutions. Some stations have new nozzles and other stations have mechanisms to dislodge or dry water that might be between the “teeth” inside the nozzle. Development continues.

If the nozzle does freeze to the car, don’t pour water on it or twist it back and forth to try to force it off the car. You may have to wait a minute or two for the temperature of the nozzle to warm up enough to remove it from the receptacle.

Questions about Hydrogen

How much of the hydrogen dispensed is renewable?

SB 1505 (2006, Lowenthal) requires that 33% of hydrogen used for transportation come from renewable sources. Page 15 (Finding 9) of the California Air Resources Board’s 2017 Annual Evaluation of Fuel Cell Electric Vehicle Deployment and Hydrogen Fuel Station Network Development (aka “the AB8 report”) states, “Currently, California’s open and funded fueling network is expected to dispense 37% of its hydrogen utilizing renewable resources, exceeding the 33% requirement of SB 1505.”

As part of the Low Carbon Fuel Standard credits for ZEV infrastructure that were recently approved (taking effect in January 2019), one of the requirements is that the hydrogen dispensed at qualifying stations must have a renewable content of 40% or higher.

California is working to increase renewable hydrogen in state. The California Energy Commission has funded three renewable hydrogen projects and a renewable hydrogen production road map in 2018. A webinar regarding the renewable hydrogen road map takes place on November 13, 2018.

What is the difference between renewable and non-renewable hydrogen?

Most hydrogen is produced from natural gas. According to data collected by the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, California facilities produce approximately one-fifth of the nation’s supply of hydrogen, which is mostly used oil refining. Renewable hydrogen is produced from solar or wind electrolysis of water, from biomass (like crop waste), or biogas (from landfills or wastewater treatment plants.) No matter the feedstock used in production, the end product is exactly the same—99.999% pure hydrogen.

Are there plans to build more stations with on-site production?

Overall, CaFCP members envision more renewable hydrogen production, although not necessarily onsite production in the state. In the Renewable Hydrogen Roadmap, Energy Independence Now states that building centralized renewable hydrogen production plants that can supply hydrogen stations and provide gas-to-power for the electric grid is a better investment than small-scale, onsite production. In addition, few gas stations have enough space for equipment needed for on-site production.

CaFCP’s Revolution calls for policies coupled with industry commitment to incentivize the transition to 100 percent renewable hydrogen, and we expect most of that will come from excess renewables, including wind and solar.

In the meantime, the Energy Commission has awarded three renewable hydrogen projects in the Inland Empire, Central Valley and Bay Area. It also recently awarded the University of California, Irvine to produce a renewable hydrogen production roadmap.

Can you provide more detail about the renewable hydrogen station at the Port of Long Beach?

The station that supports Toyota’s Project Portal trucks uses agricultural waste in a tri-generation fuel cell system. Shell Hydrogen is the station developer and operator, and the station was funded by Shell, Toyota, the California Energy Commission, and South Coast Air Quality Management District. FuelCell Energy’s tri-generation fuel cells will produce the renewable hydrogen.

Tri-generation fuel cells were developed at UC Irvine and were demonstrated at the Orange County Sanitation District for several years.

What is the difference between renewable and decarbonized hydrogen? Will California consider decarbonized hydrogen to meet renewable goals?

Generally speaking, renewable hydrogen refers to hydrogen produced using renewable sources, such as electrolysis from solar and wind power, and bio-gas from agricultural waste and sewage using tri-generation fuel cells. Decarbonized hydrogen refers to hydrogen produced using carbon capture and storage, from sources such as natural gas.

The Hydrogen Council’s vision document discusses several pathways to decarbonization, including using hydrogen in industrial processes, creating hydrogen from chemical waste, and producing hydrogen from natural gas using carbon capture and storage (CCS). The report states, “Today, 99% of hydrogen is produced through fossil fuel reforming, as this is currently the most economic pathway. Decarbonization of the current hydrogen production is challenging, but will have a positive impact on CO2 emissions and can play an important role in realizing cost declines.”

How are renewable sources of hydrogen reducing cost?

Renewables alone will not reduce the cost of hydrogen. CaFCP members are collaborating on strategies that can bring hydrogen toward cost parity with gasoline. Some reductions will come from scale (more stations, more cars) and others may come from scope, like integration with the grid.

In the short term, reductions may come from policies that incentivize vehicle adoption or encourage market-based activity. For example, the recently approved amendments to the Low Carbon Fuel Standard allowing for the generation of credits from installed capacity of a hydrogen refueling station will help in reducing costs.

Our vision for 2030 discusses the opportunities for making hydrogen renewable and the role of hydrogen in the energy transition.

Questions about Cost and Price

How do stations determine the retail price of hydrogen?

A number of factors are considered in setting hydrogen prices. Hydrogen stations estimate their operating costs—capital purchases, rent, utilities, insurance, maintenance, cost of goods sold—and amortize costs based on customers. Currently, the California Energy Commission also provides grants for operating costs.

Station developers continue to reduce costs, and Shell estimates that “50% of the current cost can be reduced in the next 2 years with small actions taken.” FirstElement Fuels has stated that building stations with more storage capacity can reduce operating costs.

How much does it cost to build a hydrogen station? What is the estimated cost of a 500/kg-per-day station?

Chapter 7 of the CEC/CARB Joint Staff Report provides cost information for all the stations that the State of California has funded since 2009 and it shows that the costs of stations continue to decline. This report will be updated in December and will include information about the stations currently under construction.

Is CaFCP working with Nel to expand the station network in California?

Yes. Nel is a CaFCP member as are many of the station developers.

If hydrogen is so good as a fuel, why does it still need this heavy government funding after all these years?

Government agencies around the world provide co-funding for hydrogen station deployment and renewable hydrogen production as part of their overall strategy to reduce fossil fuel use. Most of these agencies support multiple pathways that include fuel cells and hydrogen, batteries and electricity, renewable natural gas, public transit, and other mobility programs that reduce greenhouse gas emissions from transportation. As the energy commission states on its website “The California Energy Commission’s Alternative and Renewable Fuel and Vehicle Technology Program (ARFVTP) invests up to $100 million annually to support advancements in alternative and renewable fuels and advanced vehicle technologies…to help California reach its greenhouse gas emissions goals, improve air quality, reduce dependence on petroleum, and promote economic development.”

Can you explain how the Low Carbon Fuel Standard will help the deployment of HFS infrastructure?

The California Air Resources Board recently approved amendments to the Low Carbon Fuel Standard (LCFS) that will generate LCFS credits based on the capacity of hydrogen fueling. Station operators will generate credits in the LCFS system equal to the difference between the credits that could be earned at full station utilization (based on the station’s daily fueling capacity) and the amount generated based on actual hydrogen sales. The additional credits are intended to serve as a supplementary revenue stream during the early FCEV deployment phase. Station operators will generate credits that could provide a more-certain stream of revenue and could be an influential factor in moving the industry toward the ability to develop a station network more quickly and at larger scale, with the potential to ultimately provide significant fuel savings to FCEV customers. The amendments are expected to take effect in January 2019.

LCFS infrastructure credits will also apply to EV charging stations, too.

Will the existing stations be eligible for the proposed LCFS infrastructure credits?

Yes, as long as they officially opt into the program.

Hydrogen fuel producers have always had the opportunity to participate in the program and potentially generate credits. The latest proposed language for the infrastructure credits would allow existing stations to be eligible if they meet all other eligibility criteria.

Are non-LDV hydrogen stations eligible for LCFS credits?

LCFS is specific to fuel, not to the vehicle. All producers of renewable fuels are eligible for credits.

Questions about Vehicles

Why are companies that are not making FCEVs CaFCP members?

Although several CaFCP automaker members haven’t announced dates for introducing fuel cell electric vehicles, they are active in R&D. GM and Honda, for example, are building a joint manufacturing facility for fuel cells in Michigan. GM collaborates with the Army on fuel cell technology. Nissan is working with other automakers to fund and build hydrogen stations in Japan. Hyundai and Audi, part of the Volkswagen family, recently signed a technology-sharing agreement. These are a few examples.

Will the Hyundai NEXO be at the fall auto shows?

Yes. Hyundai’s NEXO page Is your best source of information about the vehicle release plans.

Where is the H2 ship being built and by whom?

During the webinar, we talked about the fuel-cell-powered passenger ferry that is the result of a collaboration between Sandia National Labs and the Red and White Fleet. The ship will have its keel laying ceremony soon and is expected to be completed towards the end of 2019.

Viking Cruises recently announced plans to build a fuel cell cruise ship. In June, CaFCP member Ballard signed an MOU with ABB to develop fuel cells for maritime applications.

Who are the freight operators using the fuel cell trucks at the Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach?

There are a number of freight operators that are using and will use fuel cell trucks for the various projects that have been funded over the past several years. For the recently funded Zero-Emission and Near Zero-Emission Freight Facilities (ZANZEFF) by California Air Resources Board, Toyota Logistics Services, UPS, Total Transportation Services, and Southern Counties Express will operate the trucks.

Is funding available to convert trucks to hydrogen to use local stations?

Fuel cell vehicles—cars, trucks, buses—are developed using a fuel-cell-power train; they aren’t converted from gasoline engines to electric motors. CaFCP’s research shows that it would be unlikely for a fuel cell truck to use a station that fills the car, just as today’s cars and trucks fuel at different stations or at least different dispensers.

ARB has funded pilot projects for fuel cell trucks and hydrogen stations, and we expect to see other projects funded in the future.

The 1,000-station target is quite aggressive. Do you expect an increase in subsidies to support this?

The Revolution calls for a transition from grant funding to market-based incentives, like the Low Carbon Fuel Standard, that reward early investment by private industry. It’s important that hydrogen, and other ZEV fuels, become self-sustaining without government support, however, in the early years government support and government/industry collaboration are essential.

Questions about Station Development Dates

Which Sacramento station will open first?

At this time, it is difficult to estimate.

I know you don't want to make promises and there are always delays, but rather than keep us in the dark, please give us accurate information so we know how the station is progressing.

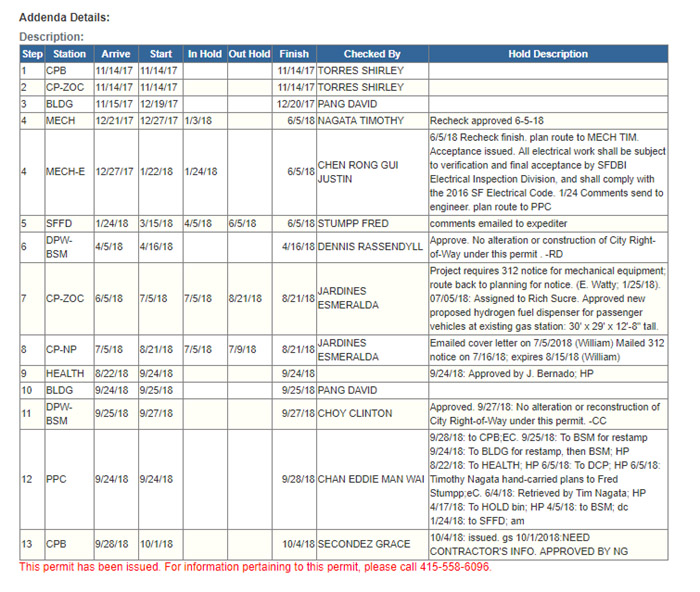

The permitting process can be long and slow. It’s not unusual for any significant building project to spend a year in permitting and during that time it looks like nothing is happening. Nearly every city and county has an online permit portal we can use to follow the process for a particular project. Some of the portals provide a lot of detail, others just give you a status. The City of San Francisco’s online portal for building projects provides quite a bit of detail.

Type in the street address, like 1201 Harrison Street, and you can see the history of permits applied for and issued. Filtered by Building, the portal shows the city received a permit application for a new hydrogen fuel dispenser on November 8, 2017. The Details page shows all the steps of the review process and that the permit was issued on 10/4/18.

With a permit issued, the station developer will work with the contractor to develop a construction schedule. At the monthly phone call that GO-Biz leads for the station developers, CEC, and CaFCP, we will get a better idea of when the Harrison Street station will be constructed. As construction starts and progresses, the station developer will provide monthly updates that narrow down the month and later the week that the station will be ready for confirmation.

We provide you with the best information that we have.

How do you track station development?

The Joint Agency Staff Report on Assembly Bill 8 defines four stages of station development. Of the stations awarded funding last year, only two are still in the first phase “grant award to permit application filing.” 14 stations are in the second phase, having filed for permits, and five stations are in the third phase, “construction.” Figure 8 on page 26 provides development timelines for the last three station awards, but the current stations are developing much faster. Our goal is to reach parity with other construction projects—about a year from design to open.

Questions about Future Locations and Stations in Other States

Are stations opening or planned for Sherman Oaks, Palm Desert, Arcadia, Highway 101, San Diego County, Highway 99 corridor, Santa Cruz, Redding, or near the Nevada state line so I can drive to Vegas?

The CAFCP station map lists all stations open and in development. A Sherman Oaks station is in development.

Station deployment planning is an important process that considers many factors. The goal is to ensure that people can drive their FCEV as they do a conventional vehicle, but we also need to ensure that the early stations have enough customers to ensure high utilization.

The California Air Resources Board in its 2018 Annual Evaluation of Fuel Cell Electric Vehicle Deployment & Hydrogen Fuel Station Network Development (pp 24-27) identified Tier 1, 2 and 3 priority area recommendations as to where to place the next hydrogen stations to reach the 200 station goal set by Governor Brown in Executive Order EO-48-18.

The California Air Resources Board created a GIS planning tool, CHIT, to help the state determine station coverage gaps.

CaFCP’s automaker members provided input to ARB and in 2017 published a list of recommended priority areas for future hydrogen stations that has been incorporated into ARB’s recommended priority areas for future state funding.

The automakers and CEC listen to the requests that the public sends through the CaFCP webinars and Facebook posts, and the input given to CaFCP staff.

What are the plans for stations in states neighboring California?

The Governor’s Office of Business and Economic Development (GO-Biz) is beginning to work with other states in addition to those in the Northeast, and we recently began preliminary conversations with stakeholders in Washington, Oregon, Nevada and Utah.

How soon will we able to use the stations in the Northeast?

Four of the stations are built and automakers are awaiting the opening of more stations before releasing vehicles. You can stay in touch with Toyota and Honda through their websites.

Why doesn’t the AFDC database show the stations in Lodi and Whippany?

It appears we had a data transmission error and now the stations are on the AFDC database.

What happened to the stations and buses used in Vancouver for the Winter Olympic games?

BC Transit demonstrated 20 FCEBs in Whistler, Canada between 2010 and 2014. Introduced during the 2010 Winter Olympic Games, it was a true test of fuel cell technology because the FCEBs formed the backbone of the fleet—20 out of 23 buses—because of the challenging duty cycle for buses with wide temperature differences between the seasons, steep grades, and heavy passenger loads during peak season. The buses fueled at 800 kg/day station in Whistler. The buses performed admirably during the technology demonstration and after four years in service they were retired. The information learned from the buses and station were critical to developing the bus fleets we have today.

Questions about Other Topics

Does CaFCP have a partner or competitor relationship with LNG and CNG? With batteries?

CaFCP’s government and industry members work with many fuels and vehicle types. We believe that reaching California’s goals for reducing greenhouse gas emissions from transportation requires a combination of technologies. We don’t have a competitive relationship with battery electric vehicles; many of our members work on and support fuel cell electric AND battery electric vehicles.

Is there any interest in or a program for hydrogen combustion engines or hydrogen blended with natural gas?

Individual companies may be looking at combustion and “hythane,” but within CaFCP we’re focused on fuel cells powered by hydrogen.

Who were the people speaking?

Keith Malone, CaFCP’s government relations and public affairs representative was the lead presenter and spoke about LCFS, the northeast stations, and other applications like trucks and ships.

Ben Xiong, project lead of SOSS and digital communications manager, spoke about SOSS, the station map, and station data.

Chris White, CaFCP’s communications director, moderated the questions and answered some of them.

Lun So, webmaster and graphic designer, helped answer the questions during the webinar.

On the next webinar, you may hear from our newest colleague, David Park, infrastructure development coordinator.